Newsletters & Travel Tips

Eland are proud to reissue this compassionate novel. First published in French in 1999, but as timely and relevant today, on a subject rarely out of the news. Binebine is one of Morocco’s leading literary voices and artists and we welcome him to the Eland list.

A writer, says Mahi Binebine, is ‘a sponge’ forever soaking up ‘rumours, passed-down tall tales and family lore.’ Like any good storyteller, Mahi Binebine is a magpie; constantly foraging the streets of Marrakech, newspapers, and what happens in his own life, for stories he might weave into his hypnotic tales. As a young boy he would cross the Djemaa el Fna on his way to school. It was then that Mahi first witnessed the lives of the artists making their living on the square: snake charmers, street performers, merchants, beggars, migrants, and the legendary Moroccan figure of the storyteller.

Read more

Jaipur is the best literary festival in the world, not because it is the biggest (it is not), nor because it is well-funded (it is not) but because it is free. Or almost free. You have to register in advance, but the five-day student pass will set back a young scholar 100 rupees, which is under £1.

This creates an audience unlike anything else I have encountered. A Jaipur audience is younger, smarter, more alert and attentive. It is opinionated, bright-eyed and stylish. Since no one buys seat tickets, if the audience feels that the speaker (be they ever-so-famous on the little screen) is underperforming, they simply rise up and go listen to someone more articulate and honest, often achieving this exit with some style, as sarees and scarves, or school blazers, are adjusted with a determined flourish. At any hour of the day there are seven simultaneous talks being held, most of them in open-sided tents within the Jaipur Festival compound, so there is plenty of choice, and plenty of freedom to move. My travelling companion and I agreed not to attend the same talks so we could double up on the already dazzling range of options. On each of the five days (Thursday through to Monday) the three biggest tents (Front Lawn, Charbagh and Surya Mahal) will host nine separate sessions, including a start-up session of a Morning Raga – classical Indian music. In the early evening there is always a raucous, high-volume and boldly-lit rock concert performed by bands flown in from Delhi or Bombay for which tickets are keenly purchased by Jaipur’s youth. For the rest, no individual, neatly numbered seat tickets are sold for any of the acts, nor are seats reserved for speakers or sponsors. So unlike our dear old, stuffy little Britain there are no veiled class distinctions in the seating, or entrance queues waiting for ticket checking, just a determined free flow of individuals. For the more popular sessions, a crust ten individuals thick can surround the packed rows of seats within the tents, all craning to get some sort of view. In the indoor halls, if there are no free chairs, the overflow audience neatly folds their legs to sit in the aisles or cluster around the stage.

Read more

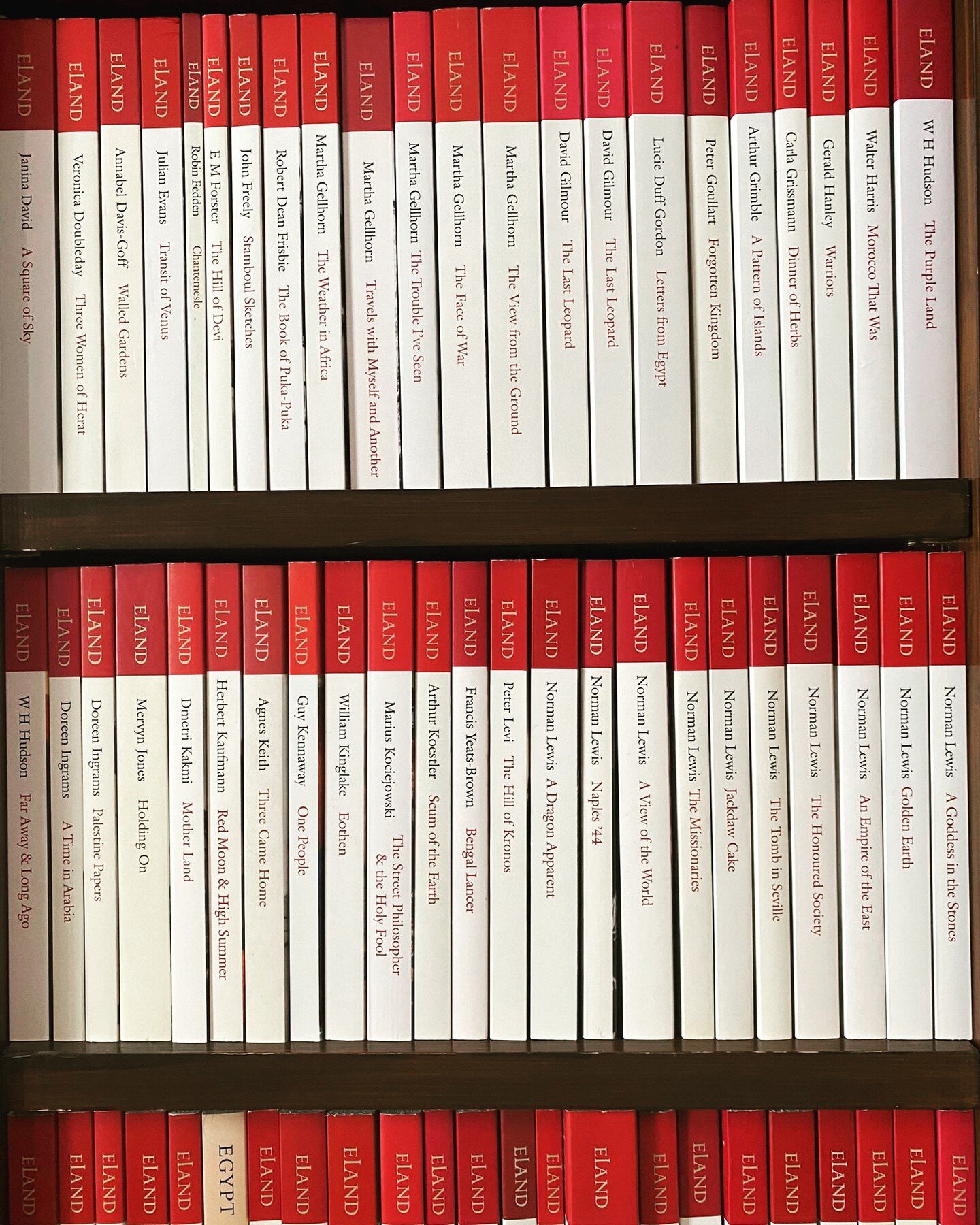

A Quiet Evening: The Travels of Norman Lewis, introduced by John Hatt

After founding Eland in 1982 with the purpose of reviving exceptional travel literature, my earliest ambition was to bring Norman Lewis to a wider readership. Therefore Eland’s first publication was A Dragon Apparent, his wonderful account of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia before those nations were engulfed in the Vietnam war. I went on to republish what I considered to be Norman’s four best books. After passing the Eland baton to Rose Baring and Barnaby Rogerson, I stayed in close touch; but, because they managed the company with such love and skill, I took a back seat. All the same, I recently beseeched them to allow me to assemble a new anthology of Norman’s best articles. They generously agreed, and this is the result.

Read more

Our December newsletter is out featuring the Eland Christmas Quiz 2024 and ideas for every Christmas stocking, including our new tote bags!

Taken from the Biographical Afterword

In this, Joe’s first book, he has already distilled his marvellous range and strides onto the authorial stage fully formed. ‘Drying saris fluttered from balconies like banners ... Whenever the train stopped, men passed by with tea urns shouting chai, chai, and there were cows sleeping on the platform and figures stretched out like corpses with grey sheets.’

He is restless, fiercely observant, and we see ‘Small sodden goats huddled in doorways with mouths shaped into smiles and cold yellow eyes ... A beggar woman mewed “Bap, mabap and touched her cracked lips”’. Joe shared his sandwiches; she ‘snatched through the window – I noticed her elegant hands’. And, intrigued, he’s drawn us in.

He is warm, funny, irreverent, unembarrassedly self-revelatory. Discreet and formidably knowledgeable, he has little interest in either dissimilation or false modesty. In conversation and on paper, swooping from one thought to another, he then makes a sharp turn for an historical digression.

Read more

After eight years working in Japan, immersing herself in its language and literature, Lesley Chan Downer set off in the footsteps of Matsuo Basho, Japan’s most cherished poet, to explore the country’s remote northern provinces. Basho’s pilgrimage to find the landscapes that had inspired the great medieval poets gave birth to Japan’s most famous travel book, rich in strange imagery and sometimes comic encounters along the road.

Being read to out loud has magic to it. Children and old people immediately understand that it means not just compelling words but close company, real engagement and an abandonment of all other distractions to engage in a shared, lived experience of now. It is impossible to be a good reader, caught up in the musical pace of your narrative and keeping a weather eye over your menu of accents, and not be totally present.

Read more

Muscat exhales history. You can sense it in the heavy hot air of summer and the light bright winter mornings, in the dusty alleys and the large crumbling square houses and it’s stored up, it must be, in some concentrated distillation in the forts of Merani and Jalali. A whiff is mixed with the breeze daily, but, like the widow’s cruse, it will not run out, not at least until the forts, and the houses, and the walls and the towers are torn down to make way for blocks of flats and offices and off-street parking.

The forts are most people’s first, and usually most lasting, image of Muscat, an image that is almost tactile, so solid are they. Coming by road up and over the last pass from Muttrah they are angled and merged almost into one, heavy and grey over the faded blue and dirty white wash of the huddled houses. From the sea they stand square in front of you, like two enormous bastions built for a suspension bridge across the harbour; but in place of the bridge there is the front line of the town, dominated by the Sultan’s palace and the British Consulate General, both gazing straight out to sea. Very proper too, for much of the history stored up in those forts and pervading the town came in ships from that same postcard blue sea, glittering peacefully in the sunshine of 1967.

Read more

When Robert Byron wrote The Station, he was twenty-two years old. Few other people write books when they are twenty-two, but then Robert Byron was not like other people. He had, moreover, written one book already. Europe in the Looking Glass, a typically ebullient record of a journey with two Oxford friends through Germany, Italy and Greece, had been published in 1926, when he was twenty-one. It is very much a young man’s book – how could it have been anything else? – yet already on almost every page there are flashes of the biting wit, the astonishing power of visual observation, the faintly mannered style with its occasional fearless plunges into the purple patch, the perceptiveness so acute as sometimes to verge on clairvoyance (such as when he writes of Bavaria that ‘it is here, more than in Prussia, that the survival of militarism is to be feared’) that were to be the hallmarks of his later voice.

‘Sensitively written, beautifully understated … this honest book is one of the few contemporary novels to show Japan as it was and is.’ The Japan Times

The Ginger Tree is one of only a handful of novels on the Eland list, yet its vivid sense of place, strong narrative drive and the engaging voice of its young Scottish heroine who recounts her experiences as a single woman in Japan in the decades leading up to the Second World War, make this book one of our bestsellers.

Read more

It is easy to sympathize with Lewis’s respect for the tough, independent, bloody-minded fishermen and the eccentricities of the impoverished landowner and priest. He became a fisherman himself in partnership with his friend Sebastian, and the lovingly detailed descriptions of diving and fishing in crystal waters are superb. The two men maintained a safe distance from the professionals, diving only for those fish that the Farol men ignored.

But any illusion that the people in these isolated villages lived an idyllic life, playing guitars and feasting on Elizabeth David dishes, is dispelled by this book. The guitar was despised, the meals were mostly stews of poor meat, and the wine was thin and acidic. Between October and March, hunkering down for the long winter, the fishermen had to live on the proceeds from their summer catch. Lewis may have made great efforts to fit in and he certainly helped many of the hopelessly innumerate locals order their affairs and avoid being cheated by the French dealers who came down to buy their fish, but he doesn’t seem to have hung around much when summer ended.

Read More

The greatest challenge in writing The House Divided was to maintain balance, not just between Sunni and Shia, but also between the three great identities within the Middle East; Arabia, Iran and Turkey. The book took several years to write (earlier drafts were three times longer), and was based upon many decades of research and travel. But finally, it was edited and complete, in September 2023. As I set off for a break in Rome, the war between Russia and the Ukraine dominated the news and, for once, the Middle East seemed quiet. I spent the day of October 7 exploring the ruins of the antique port of Ostia, where the Tiber meets the sea and where I heard news of the Hamas massacre of 1200 Israelis outside Gaza. By the time I returned to London, the Israelis had launched a revenge attack on Gaza and the Middle East was set off into a new whirlwind of violence.

Read more

Peter Mayne’s The Narrow Smile, reviewed by James Crowden

for the Royal Society of Asian Affairs

Peter Mayne (1908-1979) was a bit of a card, quick witted, suave and genteel. His English friends included Cyril Connolly, Ronald Searle, Francis Bacon and Osbert Lancaster. Just the sort of writer who gets himself deeply embedded by drinking gin and cider in London bohemian Society or drinking tea on the North West Frontier. Pathan and Hampstead codes of honourable behaviour have much in common. The greatest crime is to be boring… Peter had many friends not just in Pakistan. He spent many years in India, first in shipping in Bombay and then in Madras. His father had run a top notch college for Indian Princes - Rajmukar College down in Gujerat.

Read more

From the Introduction by Rose Baring

This beautiful album of watercolours, created during a five-month cruise to the Far East in the winter of 1896–7 on her husband’s steam yacht, is the fullest expression of the talents of my great grandmother, Mabel Ashburton.

***

So these pages and the magical glimpse they give us of the era of the steam yacht are all that remain of the Venetia. Mabel’s grandson, my father, made a private press edition of 200 copies of the album to celebrate his 90th birthday in 2018, giving them away to family and friends as a reverse birthday present. The remaining copies are now for sale to anyone who wishes to experience late Victorian travel and the world at that time from the comfort of their armchair.

Read more

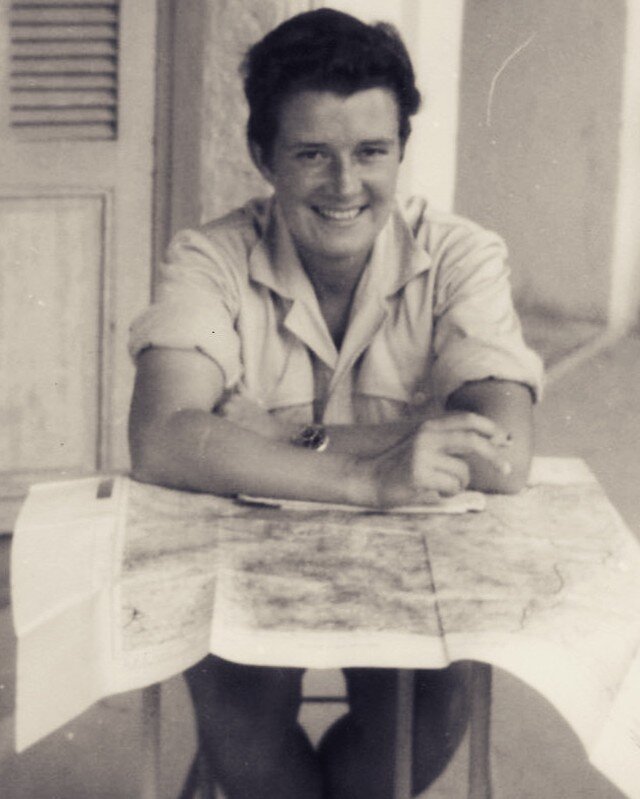

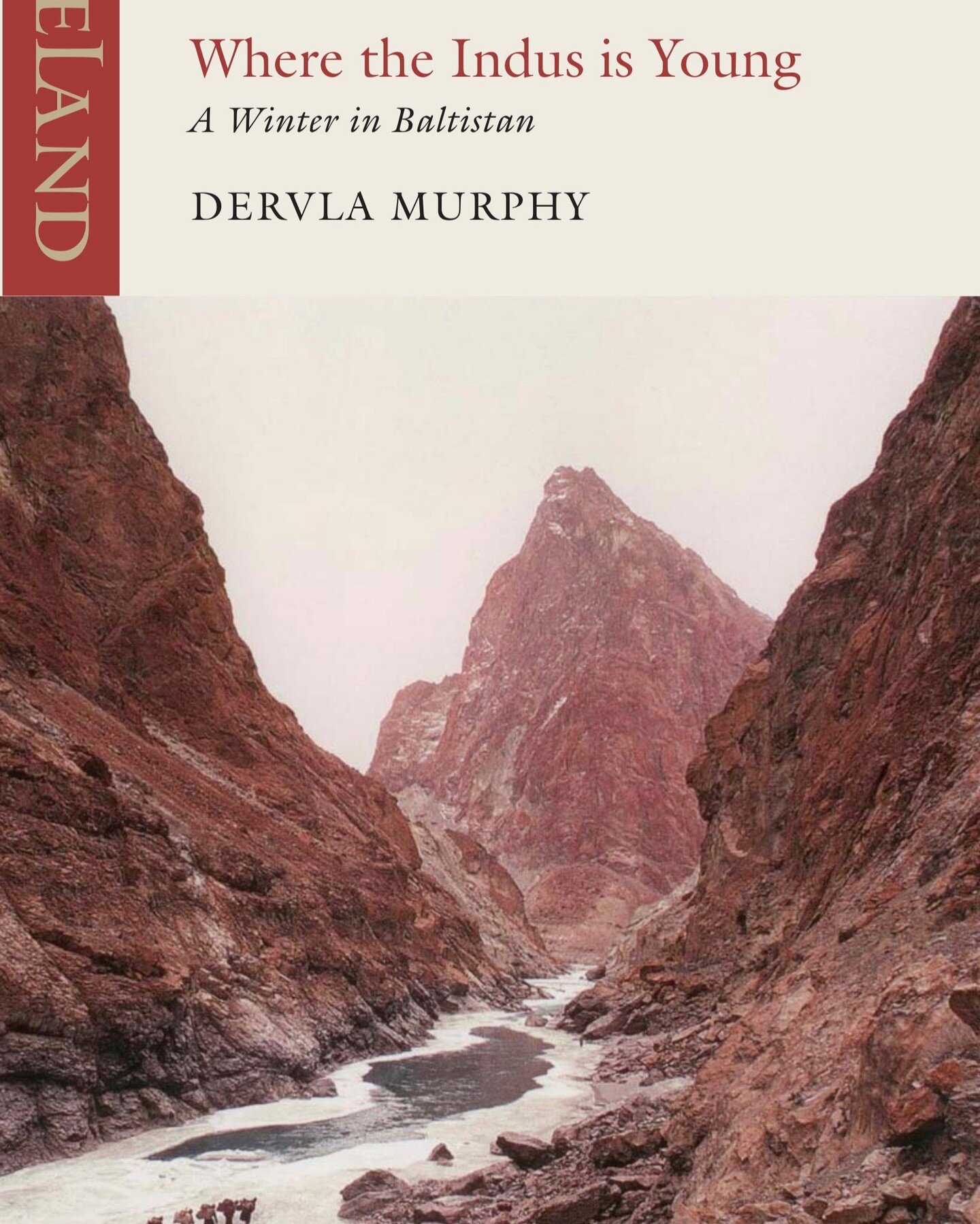

Dervla was all about books: reading books, writing books, researching books, and reviewing books – dissecting them with a scalpel. This last metaphor is apt because she said that her other chosen profession would have been that of a surgeon, if life’s randomness had led that way. If her father had found work in Dublin rather than moving to a rural town like Lismore, would Dervla have followed a more conventional educational path and aimed to become a surgeon, of which she often dreamed? Then maybe she would have been Professor Murphy, eminent vascular surgeon, instead of travel writer extraordinaire.

Read more

In 1880 Christian Watt, a woman of forty-seven who was to be a patient for many years in Cornhill, the Aberdeen Infirmary for those suffering from mental disorders, started to write down recollections of her life. She wrote on foolscap sheets of paper in pencil – pen and ink were forbidden within the institution – with a firm, clear hand. Her memory was encyclopaedic, her gift of narration superb. Before she died in 1923, she had recorded the principal events and impressions of a life of ninety years, describing folk and incident of the mid-nineteenth century in a way which, six decades later, brings both before our eyes.

Read more

I am not neutral about Don McCullin.When I was a photography-obsessed teenager, he was quite simply my God. I well remember sitting in the back row at maths classes in 1980s Yorkshire, covertly flicking through the school library’s copy of Don’s Hearts of Darkness, transported from a dull world of equations and trigonometry – taught, for duffers like me, in a shabby, paint-peeling Portakabin – to the war-torn jungles of Vietnam and Laos, the darkly barricaded streets of Famagusta and Beirut, the Killing Fields of Cambodia and Biafra. Don’s work was eye-opening, shocking, exhilarating, frightening and deeply disturbing all at once; and for a teenager it was utterly irresistible. Moreover, it spoke to a heady and thrilling world of photojournalism that I longed to be part of.

Read more

Brazilian Adventure is as fresh a story today as it was when originally published in 1933.

It began with an advertisement in the agony column of The Times: ‘Leaving England June, to explore rivers Central Brazil, if possible ascertain fate Colonel Fawcett; abundance game, big and small; exceptional fishing; room two more guns.’ Colonel Fawcett and his son Jack had embarked on a journey in 1925 in search of a supposed lost city and were never seen again. This expedition was too much of a temptation for Peter Fleming, a young

journalist with energy and an appetite for adventure.

Read more

Lewen Weldon was mapping the eastern desert of Egypt when World War I broke out. A fluent Arabic speaker, he was recruited to run a network of spies and confidential agents who were landed from a steam yacht onto the Syrian coast behind Turkish lines. He took his men to the shore in small boats at night, which also allowed him to land and conduct personal interviews before returning back through the surf. This vivid tale of adventure becomes eyewitness history as we encounter Armenians escaping the massacres, passionate Arab nationalists, resolute Turkish soldiers and a heroic network of Jewish volunteers.

Hard Lying was first published in 1926. Read Barnaby Rogerson’s fascinating biographical note on the author and his personal connection with Eland.

Read more

In Africa Dances Gorer takes the reader on an odyssey across West Africa, in the company of one of the great black ballet stars of 1930’s Paris, Féral Benga. This new edition features an afterword from Lamont Lindstrom.

Dancing Together – Black and White

Interwar Paris of the 1920s and 1930s was a honeypot buzzing with artists, writers, composers and musicians, many of whom arrived from around the world. Among these were dancer Féral (François) Benga, a Wolof migrant from colonial French Senegal, and Geoffrey Gorer (born 1905), a young graduate of Cambridge University and aspiring writer. Benga, a member of a wealthy, acculturated family in Dakar, had come to France in the mid-1920s when he was seventeen. He survived in Paris selling perfumes until he ran into a relative who admired his physique. Recommended as a cabaret performer, Benga found employment with the Folies Bergère where he became a featured dancer. He performed often with Josephine Baker, including in her signature banana dance. Modernism, and its primitivist shadow, powerfully then stimulated the city’s artistic community. Just as Picasso, Matisse and others incorporated African and Oceanic elements in their work, so did Parisian choreographers blend black themes and bodies within their productions. Dance, whether popular, jazz, or contemporary ballet, in those years combined and expressed both modern sophistication and savage vitality.

Africa Dances was published in 1935 and proved both a critical and financial success. It was also one of the most searing criticisms of the bleak reality of French colonialism to have ever been published.

Read more

A honeymoon these days is rarely the first holiday a couple takes together but it is still a significant way-post on the journey that is their life together. You’ve shed the build-up to the day itself, made a public declaration of your love, said goodbye to the mother-in-law in her preposterous hat and you are finally alone again, with the future laid out before you. It is yours to decide, yours to mould into shape. And that is why writers have been so drawn to the subject. As two paths converge to make one, how will the new, shared future be negotiated? For many of the people in this book, the honeymoon is the first holiday they have ever been on together, and the first time they have shared a bed. Here, before us, are their early, tremulous attempts to define that future.

It is not often that you get to talk with a beer-drinking prophet, so when I am asked if Eland will ever make a serious profit, I can tell them we have already banked our greatest dividend, talking the world with Dervla Murphy.

Read more

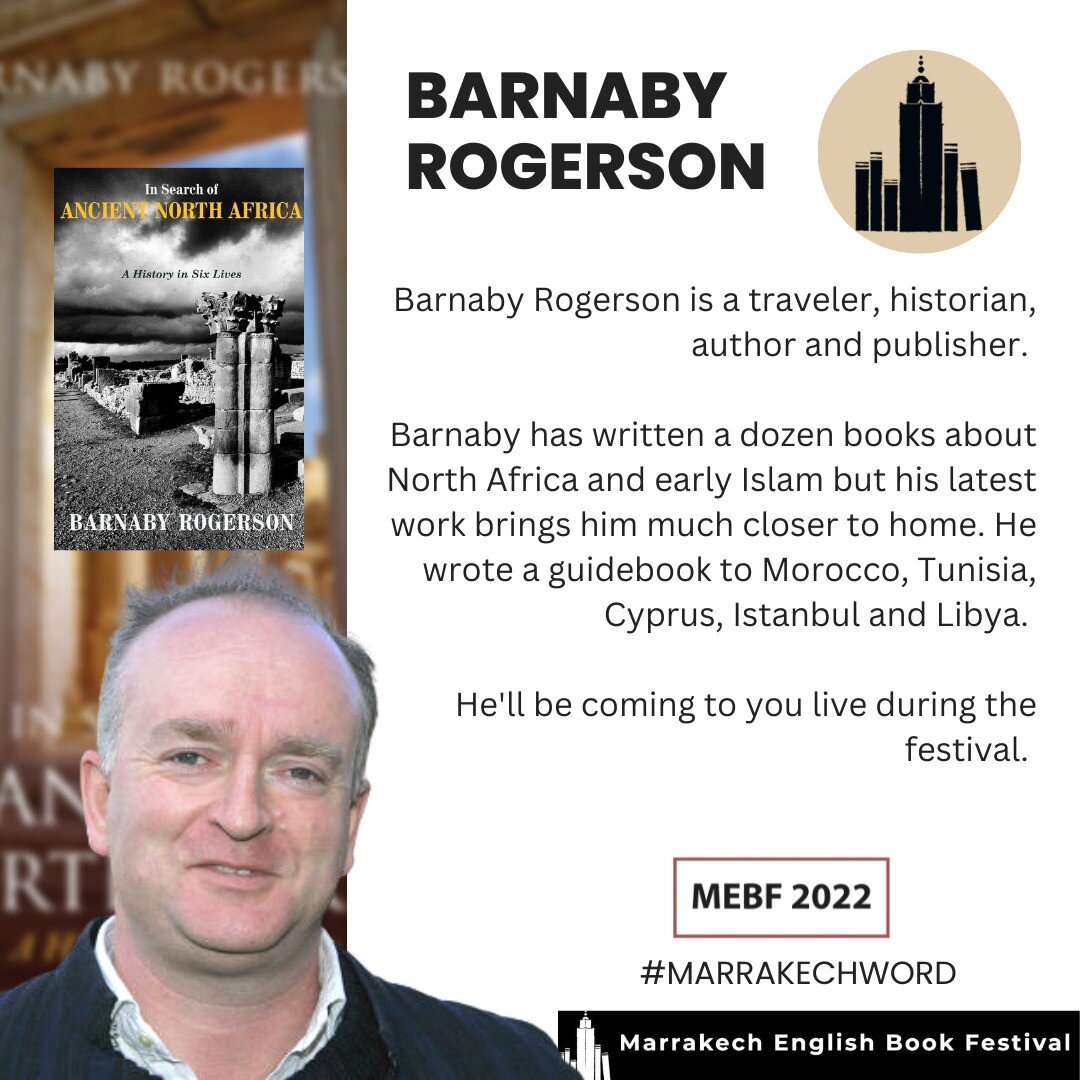

Could the world possibly need another book festival? It turns out that the answer is yes, but not for the reasons you might imagine. It’s always fun for authors to meet some of their readers after the solitary process of writing, but the inaugural festival in Marrakesh turned out to be much richer than that.

Dar Cherifa is a far cry from even the most elegant of book festival tents – one of the oldest courtyard houses in the Marrakesh medina, it dates to the 16th-century and radiates age and distinction from its ornate tiles, plaster and beautiful carved wood. No doubt rising to the challenge of the historic setting, Eland publisher Barnaby Rogerson sits on a table in the courtyard to give a breathtaking exploration of the ancient history of north Africa, ranging from Queen Dido to St Augustine and a number of Berber kings in between. The audience are amazed and delighted that anyone from Europe should know so much about their homegrown heroes, and the vibe is one of mounting mutual respect. When the afternoon call to prayer interrupts Barnaby’s flow, he sits in contemplative silence, simply acknowledging the supremacy of his host culture in a way that endears him even more. The scene is set for an extraordinary weekend of subtle exchange.

Read more

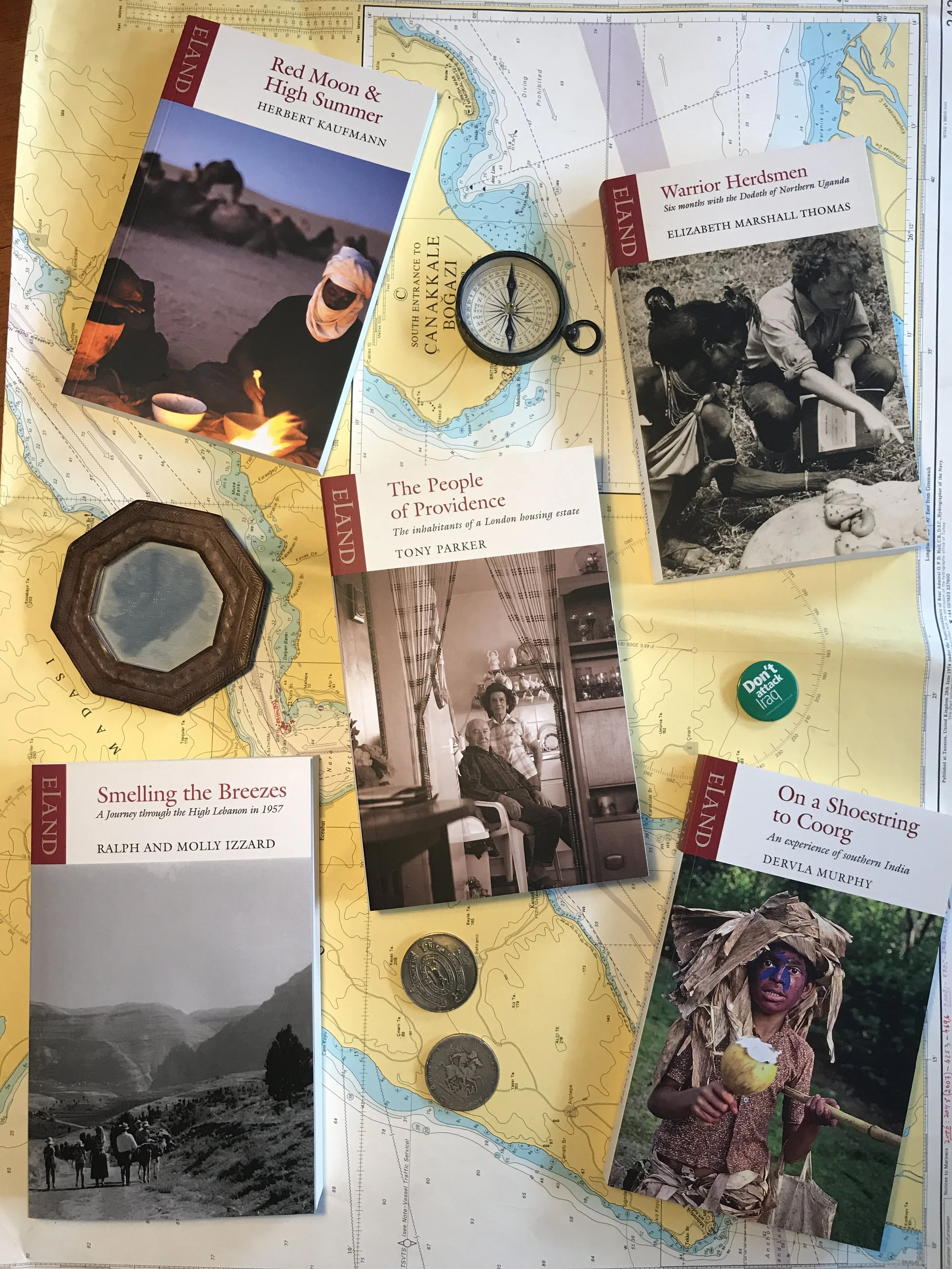

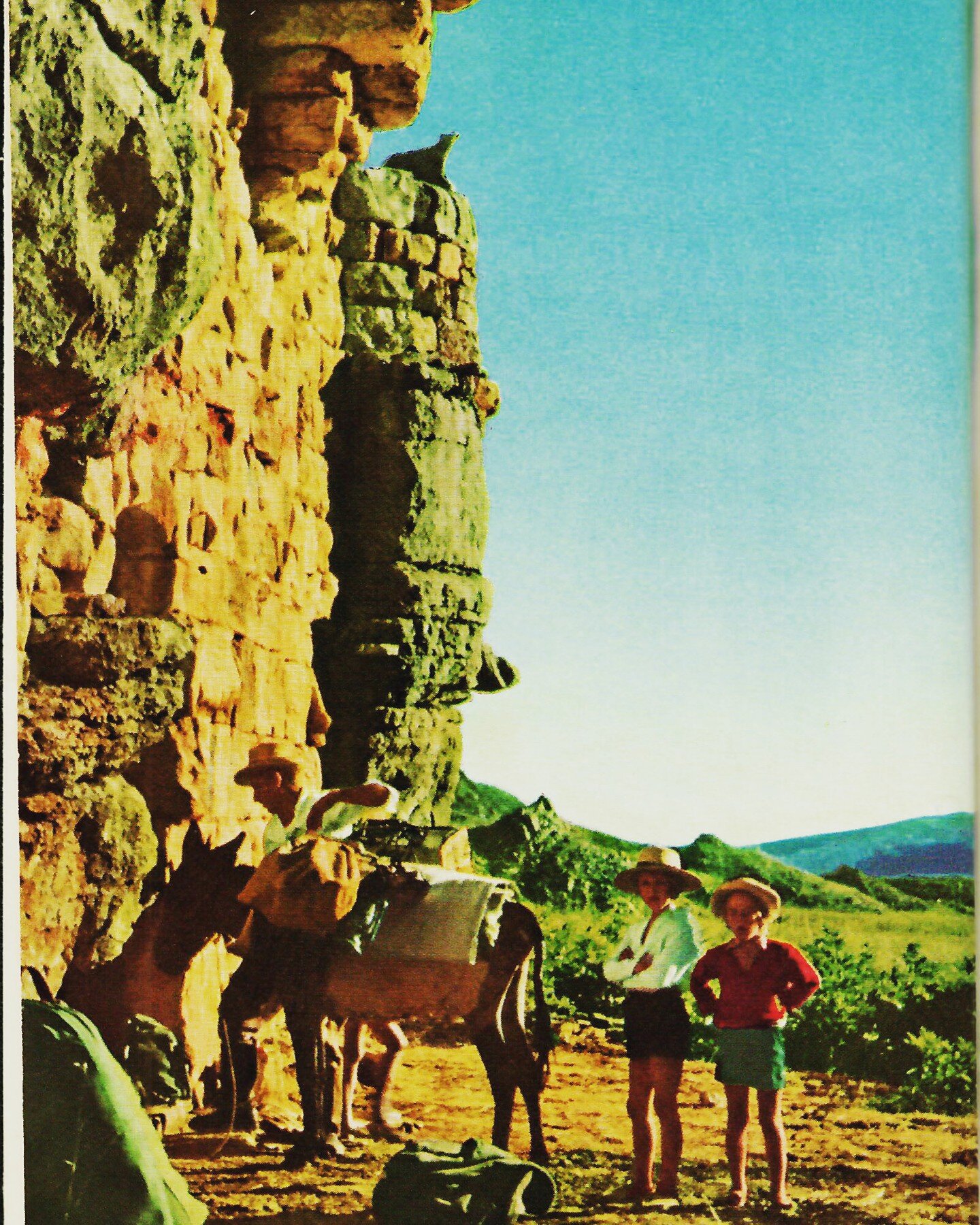

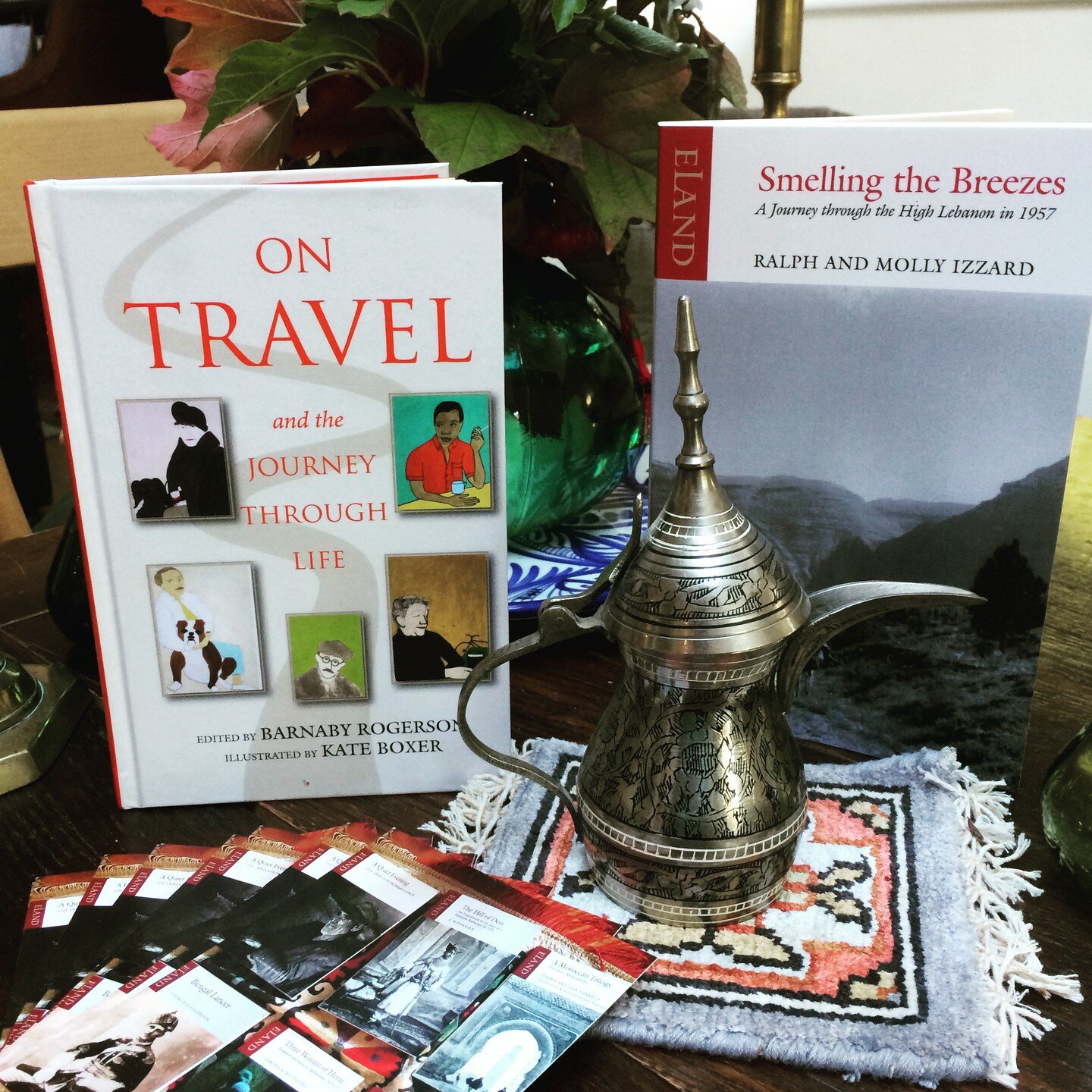

Read Barnaby Rogerson on Ralph and Molly Izzard’s trek across the Lebanese mountains in 1957 with 4 children, 2 donkeys and Elias.

‘Ralph himself was one of three role models from which Ian Fleming created the fictional James Bond. If you have ever wondered what James Bond, having settled down with Miss Moneypenny, might have been like as a father, then you need look no further.’

Jan Morris described Ralph Izzard as ‘the beau ideal of the old-school foreign correspondent … not only brave and resourceful, but also gentlemanly, widely read, kind, a bit raffish, excellent to drink with, fun to travel with, handsome but louche, honourable but thoroughly disrespectful. He was old Fleet Street personified. Not only did everyone in the business know him, but they had also known his father, Percy Izzard, the Mail’s highly respected gardening correspondent who was the inspiration behind William Boot in Evelyn Waugh’s novel Scoop.’

Such was the unusual stamp of the man who took his four young children off to walk the spine of the Lebanese mountains in 1957. Although his name is on the cover of Smelling the Breezes, it is mostly written by his wife. Smelling the Breezes was Molly’s first book and was published in 1959.

Read more

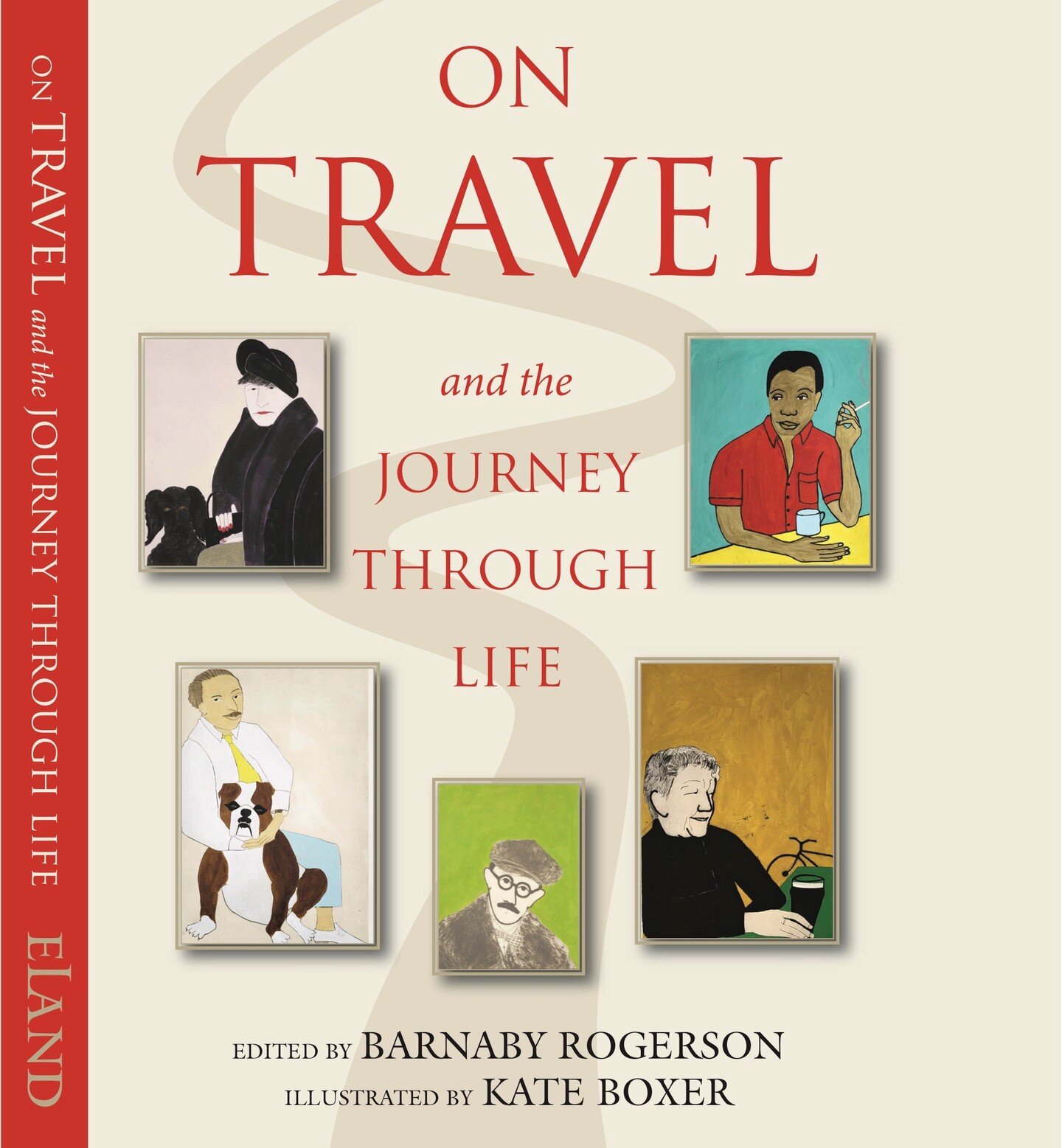

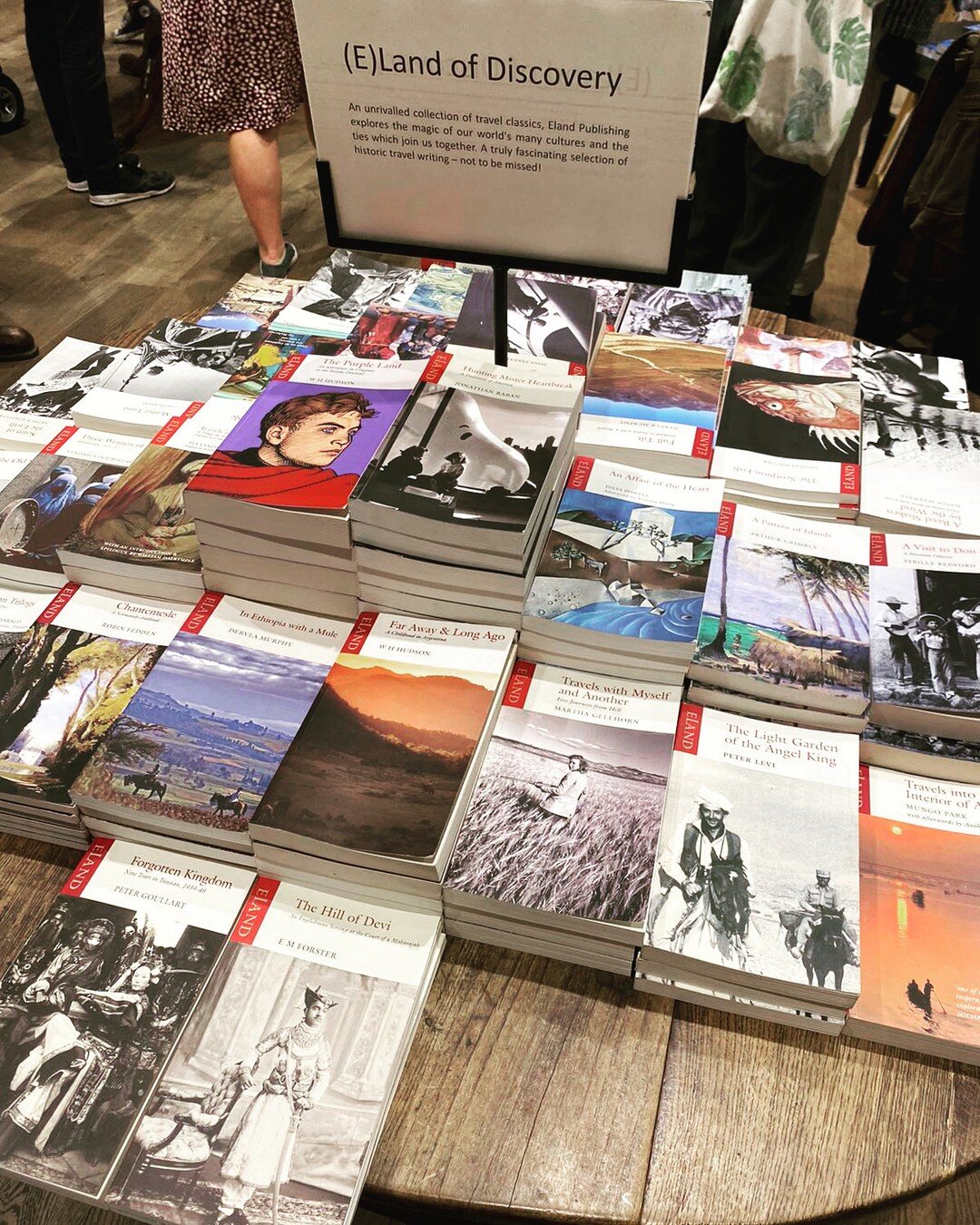

For forty years (1982–2022) Eland has been publishing travel books, driven by a fascination with human society in all its forms and a desire to celebrate those differences. There’s an exhilarating variety of alternative ways of being, of different ways to think about the world around us and our position in it. And although we can’t all take off for years to settle in a foreign land, learn the language, embed ourselves in a community and observe its complex relationships, we do all know about the liberation of leaving home.

Popular perceptions of Afghanistan have changed radically since the mid-1970s, when I lived there. Before the communist coup d’état of 1978, it was a relatively peaceful and obscure location, and during the following years of civil war Afghanistan remained inaccessible and remote. By the mid-1980s, when I had a draft manuscript of Three Women of Herat, I had a hard time convincing a publisher that sufficient people would be interested in reading about Afghan women. Now, by contrast, everyone has heard of Afghanistan as a site of ongoing conflict – a sinkhole into which vast sums of money have been poured and thousands of lives lost. Situated on the strategic crossroads of Central Asia, over and over again the real needs of this beleaguered country have been disregarded by self-interested neighbours, super-powers and Islamist groups such as al-Qaida and ISIS. Now and then ‘the plight of Afghan women’ resurfaces, but media images tend to stereotype Afghan women as downtrodden victims of abuse and violation – a simplistic message that does not reflect my own experience.

An Englishman Serving at the Court of a Maharaah

The novelist E M Forster opens the door on life in a remote Maharajah’s court in the early twentieth century. Through letters home from his time working there as the Maharajah’s private secretary, he introduces us to a fourteenth-century political system where the young Maharajah of Devas, ‘certainly a genius and possibly a saint’, led a state centred on spiritual aspirations.

1 Jan. [1913]

So many delights that I snatch with difficulty a moment to describe them to you. Garlanded with jasmine and roses I await the carriage that takes us to the Indian Theatre, erected for the Xmas season outside the Old Palace. But to proceed.

Usually when I tell someone in Britain that I live in Jamaica they say the same thing: ‘Isn’t that terribly dangerous?’ If they look dull or annoying, I say ‘Yes, very. Chances of survival are frankly low. Don’t go. Try the Dordogne.’ But if they look interesting, I say to them, ‘Not at all, unless you go looking for trouble,’ and we agree that this is true of any country worth visiting.

***

When I return to the UK, recently for shorter and shorter periods, I feel a lassitude settle on me. I don’t have to interact with the people and the environment at all times. The immigration officers aren’t flirting and laughing, no one dares dance in the street, and I am safely cocooned from anything that might harm me. I age too fast in Britain. Take me back to Jamaica.

Experience Flows Away

A couple of days later, hot, dirty and exhausted, I arrived in the outskirts of Chiang Mai in the back of a song taow. The truck stopped at a traffic light. There was a band of small boys by the side of the road, holding a bucket of water. I saw them running towards the truck, but it was still something of a surprise when they emptied the entire contents of the bucket over me.

‘It’s the beginning of songkran,’ the driver called back. ‘You’d better get used to it.’

-

RT @booksandwellies: This looks an incredibly interesting book, populated by such figures as Penelope Betjeman (née Chetwode… https://t.co/HD4r2WIwJu

-

Another outing to @The_PBS Petersfield Bookshop's 'Dead Poet's Salon' last night - discovering the life, times & p… https://t.co/39qSW17zYr

-

Neglected Books, Publisher’s Spotlight Thursday 30th March – Barnaby Rogerson discussing John Freely’s classic ‘Sta… https://t.co/bBiKeUnACs

-

Norman Lewis: The Time Traveller (1993). Lewis goes to the Baliem Valley of Irian Jaya, New Guinea, to observe the… https://t.co/NNYwRo7Sju

-

RT @MatthewAsprey: My review of #NormanLewis's A View of the World' @ElandPublishing @thejulianevans @normanlewiswrit https://t.co/M7PQcsXfAA

-

RT @ElandPublishing: “He had watched spellbound while specialist grave-robbers cleaned figurines from Morgantina, famous for moving thei… https://t.co/thdSKEFOF1

Above a curry house in Brick Lane lived Clive Murphy like a wise owl snug in the nest he constructed of books, and lined with pictures, photographs, postcards and cuttings over the nearly fifty years that he occupied his tiny flat. Originally from Dublin, Clive had not a shred of an Irish accent. Instead he revelled in a well-educated vocabulary, a spectacular gift for rhetoric and a dry taste for savouring life’s ironies. He possessed a certain delicious arcane tone that you would recognise if you have heard his fellow-countryman Francis Bacon talking. In fact, Clive was a raconteur of the highest order and I was a willing audience, happy merely to sit at his feet and chuckle appreciatively at his colourful and sometimes raucous observations.

I was especially thrilled to meet Clive because he was a writer after my own heart who made it his business to seek out people and record their stories. At first in Pimlico and then here in Spitalfields through the sixties and seventies, Clive worked as ‘a modern Mayhew, publishing the lives of ordinary people who had lived through the extraordinary upheavals and social changes of the first three-quarters of the century before they left the stage.’ He led me to a bookshelf in his front room and showed me a line of nine books of oral history that he edited, entitled Ordinary Lives, as well as his three novels and six volumes of ribald verse. I was astonished to be confronted with the achievements of this self-effacing man living there in two rooms in such beautiful extravagant chaos.

Read more