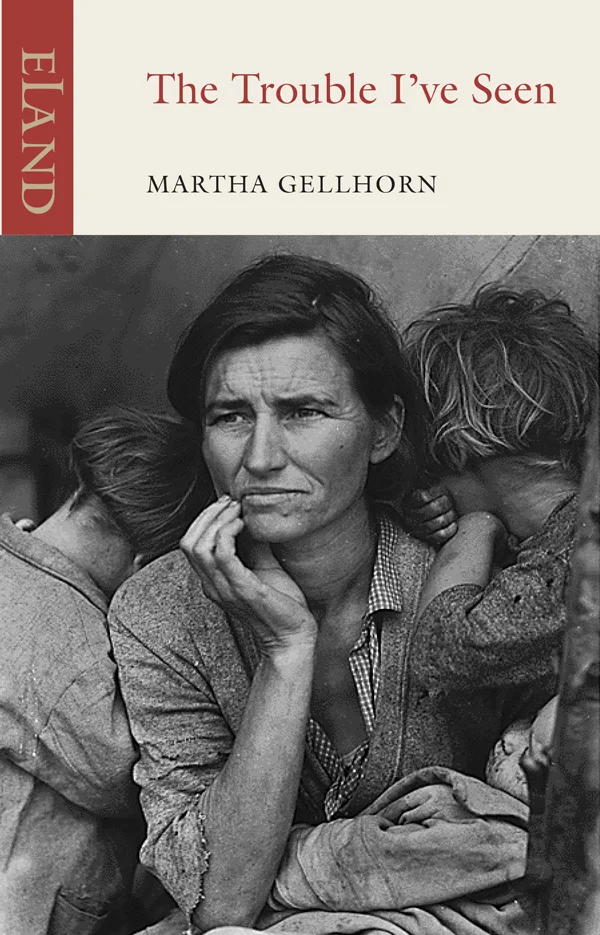

The Trouble I’ve Seen - Martha Gellhorn

The Trouble I’ve Seen - Martha Gellhorn

These four interlinked stories encapsulate Martha Gellhorn’s firsthand observation of the Great Depression. Fiction crafted with documentary accuracy, they vividly render the gradual spiritual collapse of the simple, homely sufficiency of American life in the face of sudden unemployment, desperate poverty and hopelessness. Martha was the youngest of a squad of sixteen, handpicked reporters who filed confidential reports directly to Roosevelt’s White House. They catch the mood of a generation ‘sucked into indifference’ and of young men who no longer ‘believe in man or God, let alone private industry’.

‘Lives and dances in the memory.’ - Herald Tribune

‘She achieves strength of effect without the least sacrifice of veracity, and though her work is saturated with pity never once did I find her lapsing into sentimentality.’ - H.G. Wells

The Trouble I've Seen

Introduction by Caroline Moorehead

ISBN: 978-1906011-62-8

Format: 248pp demi pb

Place: U.S.A

Author Biography

Martha Gellhorn (1908-98) published five novels, fourteen novellas and two collections of short stories. She wanted to be remembered primarily as a novelist, yet to most people she is remembered as an outstanding war correspondent and for something which infuriated her, her brief marriage to Ernest Hemingway during the Second World War.

As a war correspondent she covered almost every major conflict from the Spanish Civil War to the American invasion of Panama in 1989. For a woman it was completely ground-breaking work, and she took it on with an absolute commitment to the truth. "All politicians are bores and liars and fakes. I talk to people", she said, explaining her paramount interest in war's civilian victims, the unseen casualties. She was one of the great war correspondents, one of the great witnesses, of the twentieth century.

Her life as a war correspondent is well illustrated by two incidents. After Hemingway stole her accreditation, she stowed away on a hospital ship on 7 June 1944 and went ashore during the Normandy invasion to help collect wounded men; she was also refused a visa to return to Vietnam by the American military, so infuriated were they by her reports for the Guardian.

She was a woman of strong opinions and incredible energy. Though she turned down reporting on the Bosnian war in her 80s, saying she wasn't nimble enough, she flew to Brazil at the age of eighty-seven to research and write an article about the murder of street children. Touch-typing, although she could barely see, she was driven by a compassion for the powerless and a curiosity undimmed by age.

Extract from Chapter One

IN WHAT BECAME known as Black Tuesday, October 29 1929, the US stock market crashed. All across the country – and soon across much of the world – personal income, tax revenues, profits, prices and trade all dropped, and went on dropping. By the summer of 1933, 17 million Americans were out of work. Steel plants and coal mines were at a virtual standstill. Thirty-eight states had closed their banks, and over a quarter of a million families had been evicted from their homes. In the mining communities of West Virginia, Illinois, Kentucky and Pennsylvania, children spent their days picking through rubbish dumps and fighting over scraps of food. Skin diseases, tuberculosis and syphilis were spreading and both the Ku Klux Klan and the Communist-leaning labour organisers were finding willing recruits among people reduced by extreme poverty to apathy and a profound sense of hopelessness.

To make it infinitely worse, the Great Plains of the Midwest had been hit by a severe drought. Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Colorado and Kansas has become a ‘dust bowl’, across which rolled waves of sand and earth, filling people’s ears and noses and suffocating animals. The countryside was a desolate barren stretch of dead trees and drifting brushwood. As people ceased to be able to afford their mortgages or rent, so they lost their homes. Camps were spreading around the outskirts of cities, along the dry riverbeds and railway sidings, built out of cardboard and sacks and corrugated iron, widely known as Hoovervilles, after President Herbert Hoover. There were also ‘Hoover blankets’, made out of newspapers, and ‘Hoover leathers’, cardboard soles for shoes.

While those on the right maintained that the ‘losers’ and ‘chisellers’ were experiencing the natural consequences of their own moral collapse, and developing an unhealthy expectation of handouts, those on the left argued that the Depression was caused by the excessive, concentrated power of the elites, looking out for their own interests. Meanwhile the rising number of the unemployed was overwhelming the traditional instruments of welfare, and local organisations, once able to cope with periodic economic downturns, watched helplessly as families were thrown out of their homes, fathers lost their jobs and children went hungry.

* * *

In 1932, when the economy had reached its lowest point, Hoover lost the presidential elections to Franklin Roosevelt, who came to power determined to halt all further slide into poverty. He set up, as rapidly as possible, the administration of relief on a scale never before attempted. Under a first New Deal, a Civil Works Programme was established under powers granted to him by the National Recovery Act, intended to stimulate demand and provide work and relief through increased public spending. Within four months, four million people were back in work. A Public Works Administration followed, employing people to build bridges, parks and schools. A second New Deal added social security, a national relief agency and strong stimulus to the growth of labour unions. During one of his early fireside chats, Roosevelt told Americans that the only thing they had to fear was ‘fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyses needed efforts to convert retreat into advance’. His campaign song was ‘Happy Days are Here Again’.

To put his plans for relief and the recovery of the economy into action, Roosevelt appointed a brains trust of practical and imaginative New Dealers. One of these was a crumpled, argumentative man called Harold Hopkins, whose eyes bulged and who chain-smoked and drank too much coffee. In New York, Hopkins had helped create one of the first public employment programmes in the country, before drafting a charter for the American Association of Social Workers. Roosevelt summoned Hopkins to Washington and asked him to administer a vast programme of public relief, under the name of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. FERA was given $500 million to help states meet their relief needs, for every dollar of which three dollars of public money from other sources would be spent. A further $250 million was held as a discretionary fund for Hopkins to allocate to states where needs were too great and funds too depleted.

As an administrator, Hopkins was creative, sympathetic and driven. He was fortunate that when he arrived in Washington, there was no bureaucracy and no model for him to inherit. He could pick and choose the people he wanted and he could also experiment far more quickly and radically than other New Dealers. Until that moment, relief had been the responsibility of states. Hopkins was entering uncharted waters.

His was also one of the toughest assignments of the New Deal. He had to understand, and respond to, not only what was happening across the US, but provide data to the President and Congress, and be aware of what other New Dealers were doing. To assist him, he was given a division of Research, Statistics and Finance. Soon he was complaining that he was drowning in facts, yet knew very little about the human tragedy of unemployment, what it was actually costing in terms of broken families, alcoholism, disease and hunger. He wanted something more, something intangible and descriptive, something that would tell him what it felt like for a man to lose his job, his savings and his house and to watch his family sink into misery. Only then, he said, would he really be able to take the pulse of the country and devise a sound relief programme for the ‘third of the nation’ that was ‘ill-nourished, ill-clad, ill-housed’.

And so, in the summer of 1933, a remarkable venture was born.

Hopkins began by hiring as chief investigator into the ills of the Depression a tough-minded, overweight, erratic 41-year-old reporter called Lorena Hickok. The daughter of a travelling butter-maker, who had beaten her as a child, Hickok left home at 14 to work as a hired girl until rescued by a cousin who helped her through school. Joining the Minneapolis Tribune as a cub reporter, she became one of the first women to be employed by the Associated Press. Hickok, who had been responsible for introdu-cing Eleanor Roosevelt to the American public, and had since become very close to the First Lady, had bright blue eyes and wore raincoats and hats with wide brims and vivid red lipstick. She played poker and drank Bourbon with the boys. ‘Don’t ever forget’, Hopkins told her, as he sent her out to observe and report on the effects of the Depression on the American people and the success of his relief programmes, ‘that but for the grace of God, you, I, any of our friends might be in their shoes.’

In August 1933, Hickok set out from Washington in a car she called Bluette. She had been given $5 a day for her expenses, and $0.5 per mile for Bluette. ‘Since we have not discussed as yet the form my reports to you are to take,’ she wrote to Hopkins, ‘I’m going to give you the first one in the form of a letter, telling you where I have been and what I’ve seen this week.’ It became the model for her subsequent 120 reports.

Over the next 18 months, Hickok visited every state in the US except for the North West. It was not unusual for her to travel 2000 miles in a week, writing up her reports, which ran to several thousand words, at night on her typewriter in her motel room. Her style was breezy, evocative and free of cant; she quoted at length conversations with workers, families, reporters, employers, industrialists and union leaders. ‘Cheer up. I’ll be brief,’ she wrote from South Dakota on November 7 1933. ‘It’s been a long day and I’m tired.’ Normally she posted her reports, but when she encountered an emergency – as in the Midwest, where she found that drought, dust and grasshoppers had wiped out the crops – she telegraphed them.

What Hickok had to say was grim. From Puerto Rico, on March 20 1934, came a description that would be repeated, in one form or another, from states all across America.

No one could give you an adequate description of those slums. You’d have to see them, that’s all. Photographs won’t do it, either. They don’t give you the odors. Imagine a swamp, with stagnant, scum-covered, muddy water everywhere, in open ditches, pools, backed up around and under the houses. Flies swarming everywhere. Mosquitoes. Rats. Miserable, scrawny, sick cats and dogs and goats, crawling about. Pack into this area, over those pools and ditches as many shacks as you can, so close together that there is barely room to pass between them. Ramshackle, makeshift affairs, made of bits of board and rusty tin, picked up here and there. Into each room put a family, ranging from three or four persons to eighteen or twenty. Put in some malaria and hookworm, and in about every other house someone with tuberculosis, coughing and spitting around, probably occupying the family’s only bed.